Why I support all three, but chose to live in the monarchy

This Wednesday, February 11 is the culmination of Iran’s ten-day celebration of its 1979 Islamic revolution, which birthed the world’s first Islamic Republic. Millions of Iranians will be parading in the streets carrying flags, images of the founding Supreme Leader (Khomeini) and current Supreme Leader (Khamenei), and signs celebrating the Islamic Republic’s achievements—as well as revolutionary slogans including the notorious hardcore ones: “Death to America” and “Death to Israel.”

What Westerners don’t understand, thanks to their lying media, is that Iran’s pro-government pro-Islamic-Revolution demonstrations are absolutely gigantic, utterly dwarfing the comparatively minuscule anti-government demonstrations that periodically make the news. The last time I visited Iran—in February 2023, shortly after the anti-hijab protests that generated wall-to-wall coverage in Western media—I saw the public squares where the Iranian feminists had gathered, and was shocked at how small those protests had been. The biggest one, as I recall, had attracted no more than several hundred people. Compare that to the millions who turn out for pro-government counter-protests, or the five million who pour into the widest avenues of Tehran every February 11 to celebrate the Islamic Revolution.

I have been in the middle of such crowds of four or five million pro-Revolution Iranians, and it’s a great feeling. I’ll never forget sharing a laugh with some folks carrying a “Death to America” sign who asked me, the token American, whether I thought that slogan ought to be retired. (Iranians have nothing against Americans, it’s our government they don’t like.) I told them they can do what they like with “Death to America,” as long as they never, ever even consider giving up “Death to Israel.” That, after all, is a slogan that all sensible people, everywhere in the world, can agree on.

Alongside all those millions of Iranians, I count myself a strong supporter of the Islamic Revolution and the Islamic Republic it created. The Revolution liberated Iran from foreign colonial domination. It established a genuinely sovereign nation—one of the very few left in the world.

Thanks to its complete sovereignty, Iran is free to oppose the genocide of Gaza—and to offer moral and material support to those resisting the genocide. That alone sets the current Iranian government, alongside its Yemeni ally, head and shoulders above all other governments worldwide.

Clearly the Iranian system of government, and the leadership it has produced, is by far the best in the world. As classical philosophy reminds us, the whole purpose of governance is virtue. And the Iranian system has produced leaders virtuous enough to sacrifice their material and egoistic interests in service to what is good and right and just. Their lives would be easier if they sold out and appeased the genocidal Zionist oligarchs who rule the West. They’d have it made if they’d just accept an appointment with the likes of Epstein. But they refuse. Instead, serving virtue and justice and honor, they resist.

Islamic Iran is to governments what Thomas Massie is to the US House of Representatives.

And it isn’t just Gaza. The Iranian leadership, or at least the best part of it, remains committed to the abused and downtrodden, the Mustazafin, wherever they may be. By virtue of that commitment, the Islamic Republic has earned the enmity of all powerful ungodly forces, all abusers and exploiters. They have also earned incomparable baraka, or blessing-energy. May God continue to bless their heroism and protect their amazing achievements.

Islamic Republic: A New Idea

Even Foucault, that brilliant and degenerate atheist, understood that the Islamic Republic was something new under the sun. Prior to 1979, conservative forces had always claimed God and Tradition for themselves, while revolutionaries sought freedom from such antiquated notions. But the Iranian Islamic Revolution was the first major uprising againstWestern-style “freedom from God.” It represented an attempt by Imam Khomeini, an Islamic philosopher-king, to design a system of governance in accord with both Islamic and philosophical ideals. And as he saw, Islam and philosophy are in agreement: The purpose of government is to establish rule by the virtuous, and avoid or at least minimize rule by the vicious.

Khomeini saw that Western-style democratic republics had enjoyed a certain success. But he understood that the classical philosophers’ distrust of the demos, the mob, was well-founded, and that guardrails needed to be established to prevent democracy from degenerating when the mob occasionally swerved to follow its basest instincts. To that end, an aristocracy of virtue, but elected rather than hereditary, was essential. Hence the bifurcated structure of the Islamic Republic: A normal Western-style democracy on one side of the aisle, complete with a president and prime minister and parliamentarians; and the Platonic/Islamic guardians of virtue on the other side, headed by a Supreme Leader elected by a Guardian Council of virtuous notables, themselves elected by the people.

The philosophical and theological underpinnings of the Islamic Republic are fascinating, and far too complex to explore in detail here. If you’re interested, I highly recommend the works of Blake Archer Williams, an American in Tehran who has been writing and translating about such topics for many years.

Unfortunately, no system of governance is perfect. Nor can mere external governance ever fundamentally change human nature, caught as it is between immense potentials for both good and evil, not to mention the base triviality of ubiquitous self-interest. There is corruption in Iran, just like everywhere else. The difference is that thanks to the Islamic Revolution, there is a powerful faction in Iran pushing for, and to some extent realizing, virtuous governance. That’s why the world’s most evil people are the Islamic Republic’s inveterate enemies.

Why I Also Support the (Late) American Republic

The American experiment—another revolutionary democratic republic—was also a great idea. While most of its leaders were deists and freemasons, not all of them were entirely devoid of virtue. Classical deism held that man is the vicegerent of a good but stand-offish God, who gives us complete freedom to rule this world as we please, without hope or fear of His intervention. A ruler’s duty, the deists argued, is to rule virtuously, the way the Good Lord would rule if He were here ruling us—which, for better or worse, He is not, since after creating the cosmos He took a hike and has not been heard from since.

The American experiment involved “checks and balances” designed to prevent power from devolving into despotism, as is its wont. The most important of these was the Bill of Rights. Even today, with the American system on the verge of collapse, a vestigial understanding of the Bill of Rights has prevented the American authorities from imprisoning people who seek the truth about World War II, as happens in many of Uncle Sam’s vassal states.

My Catholic philosopher friend Peter Simpson persuasively argues that the American system never really succeeded at checking abuses of power, because it was “set up to fail” by the federalists, who secretly favored tyranny. Be that as it may, I think the combination of the Bill of Rights and the system of competing branches of government (alongside competing federal, state, and local governments) has enough virtues that it ought to be strengthened, not abandoned. In other words, rather than abandon tradition and Constitution in favor of King Trump, or revolutionary socialism, or whatever, I would support returning to a more traditional American system by rigorously applying the Constitution and Bill of Rights. We ought to annul all the unconstitutional powers, especially war-making powers, that the presidency has stolen; terminate the ridiculous practice of “executive orders” carrying force of law (only Congress can legislate); return to the traditional understanding that local and state governments are the full equals or superiors of the feds; re-establish Constitutional currency by nationalizing the ill-gotten gains of the Rothschild-headed usury cartel behind the so-called “Federal Reserve” (which is neither federal nor has any reserves); put some teeth back in the Bill of Rights; and generally overthrow the unconstitutional oligarchy that has surreptitiously replaced Constitutional democratic-republican governance in America.

Why I Also Like Monarchy, Moroccan Style

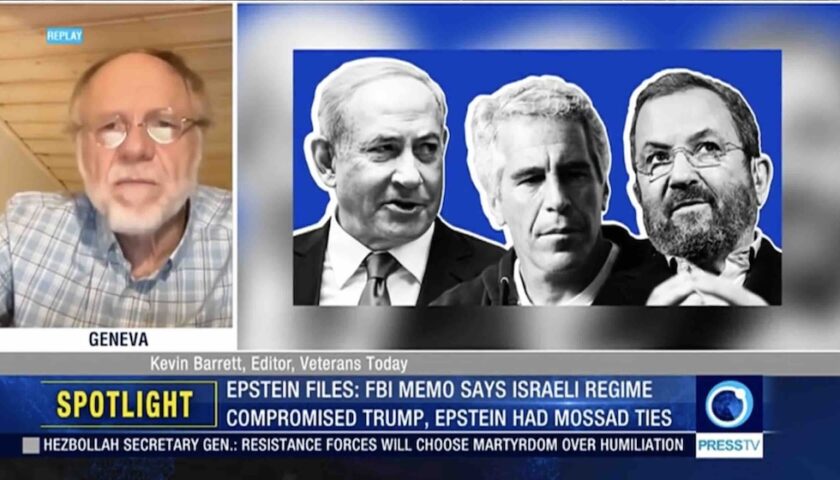

The oligarchy that has largely overthrown Constitutional governance in America is unbelievably evil, as the Epstein files show. (Those files, of course, are just the tip of the proverbial iceberg.)

Life under such an evil regime grew increasingly intolerable, which is one of the reasons I moved to Morocco in 2023. Since I have just sung the praises of two republics, one living and one moribund, I’ll now explain my generally favorable impression of monarchy, Moroccan style, and why I like it much better than most other monarchies, such as those in the UK and the Gulf petro-states.

First, to understand Morocco’s monarchy, you need to understand that it has two major historical roots. First and most importantly, it is the successor to the series of monarchies that have ruled this part of the world, the northwestern corner of Africa (sometimes including the Iberian peninsula) since the founding of the Idrissid dynasty in 788.

Morocco’s monarchy represents more than 1200 years of historical continuity. That’s an unusually rich civilizational heritage. Had Moroccans opted to ape Westerners by replacing their monarchy with a secular democratic-republican system when they achieved independence from French and Spanish colonialists in 1956, they would have been severing themselves from their own traditions and the wellsprings of their identity.

The other source of the Moroccan monarchy’s baraka (blessing-energy) and legitimacy is its identification with anticolonialism, in the person of King Mohammed V, the central symbol of the independence struggle. Reduced to a figurehead by the European occupiers, then-Sultan Mohammed V delivered the historic Tangier speech of 1947 calling for independence and unity with the soon-to-be-decolonizing Arab world. This remarkable king, one of the great figures of the postwar anticolonialist movement that freed the Global South from European tutelage, was clearly the deciding factor in Morocco’s choice to remain a monarchy.

So the Moroccan monarchy represents continuity both with the nation’s deep historical roots and its birth as a modern nation during the anticolonial era. That historical continuity largely explains why Morocco’s post-independence governance compares favorably to maghrebian neighbors like Algeria and Tunisia, which made too many concessions to European-style modernity in their transformations into relatively secular, military-dominated republics.

Moroccan-style monarchy is a religious office. Mountains all over Morocco are painted with the slogan: Allah, al-watan, al-malik (God, country, king.) And people are quick to tell you that this is the proper order: God comes first, the nation is second, and the king third.

It is also a symbolic office. The monarch represents the sovereignty of Moroccan men, whose primary submission is not to other men, but to God. Each head of household is a sort of king, and sacrifices a sheep each Eid, just as the king of the larger family, the nation, acts as national head-of-household by sacrificing a sheep on behalf of all Morocco.

Morocco’s foreign policy, especially during the past few years of genocide, has not been self-sacrificingly virtuous in the way Iran’s has. But competence is itself a virtue, and the Moroccan monarch is surrounded by relatively competent (if occasionally venal) advisors. Like China, Morocco is playing the long game. It is seeking a “peaceful rise” based on economic performance, and to achieve that it has opted to avoid confrontation with the evil, genocidal Western Zionist oligarchy. (Everyone here loathes Zionism and understands the game that’s being played.)

Moroccan tradition, including the monarchy, is inseparable from the local interpretation of Islam, which I find congenial. Sufism, or Islamic mysticism, has a thousand-year history here, and is still alive and vibrant in ways that other great mystical traditions, including Western ones, are not. The Minister of Religion, Ahmad al-Tawfik, is a historian who understands the centrality of Sufi Islam to Morocco’s culture and identity, and sponsors and encourages Sufi groups. Though governments of several countries attempt to use Sufism, Morocco is really the only nation with an actively pro-Sufi government.

Do I Contradict Myself?

So I like Iranian Islamic republicanism, American Enlightenment republicanism, and Moroccan monarchy. Most people find those three political approaches wildly divergent, not to mention irreconcilable. Am I being incoherent?

Perhaps. If so, a fellow American Unitarian, Ralph Waldo Emerson, has a word in my defense: “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.”

But let’s not forget that the outward trappings of governance are just the means to an end: the rule of virtue. Brainwashed Westerners often seem to believe that “democracy” is an end in itself, that governments are good or bad based on how “democratic” they are. That is, of course, ridiculous. A genuine democracy, if such a thing were possible, might elect virtuous leadership, in which case it would be good; or vicious leadership, in which case it would be bad. But in neither case would the fact that the mechanism is democratic matter. What matters is the outcome, not the mechanism; what matters is virtuous governance, not how we get there.

And in most cases, it seems to me, nations will get better governments if they adhere to their own traditions. Post-revolutionary China’s government, for example, has gotten better as it has grown less communist and more Confucian, and Russia’s is improving as it too substitute indigenous traditions for communism. As for Iran and Morocco, both are finding their different ways back to their own interpretations of Islamic traditions.

Meanwhile the USA is dying, its lifeblood drained by a parasitical oligarchy whose most profound loyalty is to an entirely foreign, unusually noxious entity. Its best and only hope is to return to its Enlightenment republican traditions, whatever their limitations and however feeble they may currently seem.